Chapter 20

Captain Safety

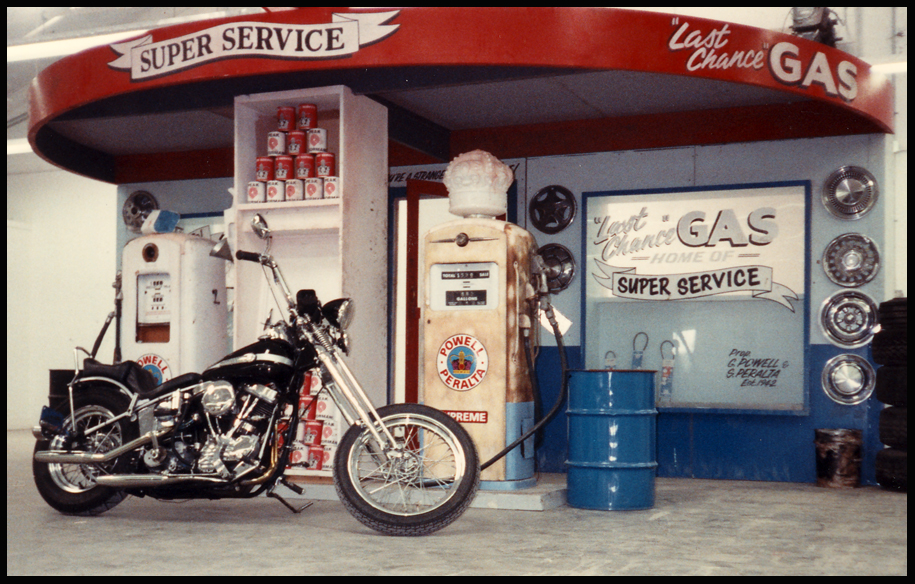

Besides the skatepark elements, there had been some fun stuff to build for the trade shows. One was an elaborate mockup of gas station; walls covered with old hubcaps, a pump island with vintage gas pumps and oil can racks, a big red canopy, with the triple-P Powell-Peralta logo spinning slowly on top. The theme was "Super Service," and all our sales reps in the booth were dressed as gas station attendants.

In addition to those corny trade shows, Facilities sometimes made props for the videos. For the 1989 video, "Ban This," our creations took me back to my own homemade skate scooter when I was 10 years old. They were well-made versions of the peach-box-on-a 2" x 4" scooter, except instead of two halves of a clamp-on roller skate from the 1940's, in the late 1980's, we had Independent trucks, Powell-Peralta urethane wheels, Bones Swiss ball bearings: the Mercedes-Benz of the Peach Box Scooters. They weren't gray this time, but olive drab army green, matching the theme of a recent trade show. We called them Armored Personnel Scooters.

As time went on, my duties were expanded into more mundane, less fun factory management tasks, and I had less time to be involved with the SkateZone building. I was put in charge of fire prevention, hazardous materials and a company-wide safety program. That kind of made me the in-house building inspector: the Sheriff of PCHQ. I took to wearing my gold "steal-your-face" skull with lightning bolt Grateful Dead tie tack on my shirt like a badge. When the fire department assigned us our own fire marshal to oversee our compliance factory wide, turned out he was a Deadhead too. We got along famously, but he never cut us any slack, and I never asked him to. He would give me a heads up if I were missing something, like if he spotted a cheaper or easier way of accomplishing a result. We teamed up to make the plant a tight ship.

One of the things I had to do was compile an archive of Material Safety Data Sheets, MSDS. There has to be on file an MSDS for every chemical or material in use in the entire factory, so if someone swallows it, or breathes its fumes, or it catches fire, we can look up what's in it right now. I had to call or write to manufacturers to chase down the required paperwork, and keep it all in a big binder. MSDS was a system that had just come into being in the mid 1980's for manufacturers, and some companies were unaware of the OSHA regulations. At one company, skeptical people I spoke to on the phone kept transferring me up their chain until I reached the CEO in a meeting with some of his managers. They put me on the speakerphone and grilled me about this so-called MSDS thing, and why I needed to know what was in their product. They thought I was a competitor trying to steal their trade secrets.

I took a night course in Hazardous Materials Handling at the nearby UCSB extension, so that I could have full knowledge of our situation and how our company fit into the required regulatory system. Others taking the course were a number of employees of Chevron Oil's local operations. Chevron at the time was running TV ads portraying the company as a protector of the environment. A blue butterfly fluttered over a seaside sand dune. A chain-linked fence had been erected to separate 2 acres of dunes from the 1000-acre El Segundo refinery, site of many, many leaks, spills and explosions, polluting the air and the groundwater since 1911. A voiceover asks, "Do people really go out of their way so a tenth of a gram of beauty can survive?" The fuzzy, warm feel-good voice answers itself, "People do," proclaiming themselves saviors of the endangered "El Segundo Blue."

The Chevron employees were pretty funny whenever the topic under discussion somehow produced a straight line. Sometimes by accident and sometimes on purpose, the instructor would phrase the current topic in a rhetorical question. "Do some toxic waste producers cut corners and cheat on disposal regulations to save money?" The Chevron managers would chant their punch line in unison, "People do," and cackle cynically.

Then there was the mandatory company safety program. Companies with even a few employees are required to have an active program to keep the workplace safe and the workers safety conscious. In the construction world, every small contractor is supposed to gather his crew periodically for a "tailgate meeting" to discuss safety matters, but they often don't bother.

Whenever it turned out that I was asked to conduct a safety meeting, my idea was to bring everybody into the awareness that 'shit happens" by going around the group and telling our goriest construction accident stories. It's amazing how many people get shot with pneumatic nail guns, often in the head. Those things can be set to "bump fire,' so that if you continuously hold the trigger down, it will fire a nail when you bump the tip against the wood and you can go faster. So if you're coming down the ladder with the trigger still pulled after nailing off some framing, your buddy is standing there holding the ladder and you're both looking the other way, BANG! He's got his hard hat nailed to his skull. I have shot one of those framing nails into my finger, cut another fingertip with a Skilsaw, fallen from high places, but I still have all my parts. Some of the craftsmen I admired most had shortened fingers due to a momentary misjudgment in the use of power tools. One moment, ZIP! and your fingertip is gone forever. No putting it back on, it was turned to hamburger. If those kind of stories give you the willies, that's the goal. Once everyone had gotten the willies, the safety meeting had served its purpose. Moving on.

In the PCHQ setting, that kind of safety meeting was appropriate for the production workers in their environment of powered machinery, but the office staff and cubicle workers have different hazards. The most common office accident is the bottom drawer of a filing cabinet is left open. Who knew? The drawer is left open and someone carrying a piece of paper or something doesn't see and trips over it.

We learned a lot about Ves' past when we took that Noodles tour to Nor Cal. After we left Derby Park in Santa Cruz, he guided us up the Loma Prieta Ridge, a small, forested mountain range running up the peninsula toward San Francisco. He had been a firefighter and driver for Cal Fire in this area, and had stories to tell about driving their equipment through impossible terrain. After that he had worked as an ambulance driver until he couldn't take it anymore. Responding to traffic accidents, he said, you get used to the gore, and the physical pain you're witnessing, and even the death; you have your training for that and you do your job. The thing that weighed the heaviest on ambulance drivers is the grief of the survivors. Ordinary people had been driving along on an ordinary day, when, BLAM! Suddenly their companion, or their parent, or child, or spouse, is dead. That's the hardest pain to witness. Or to do anything about.

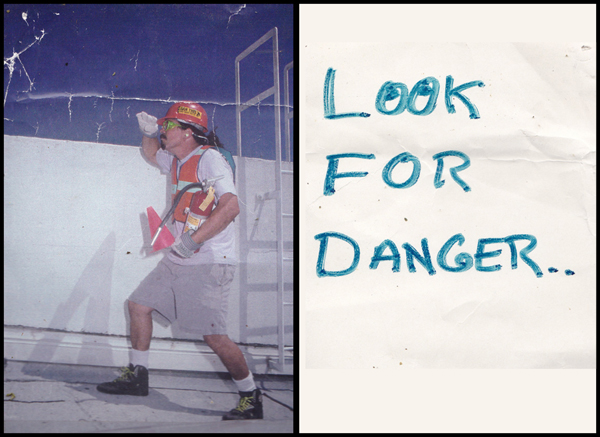

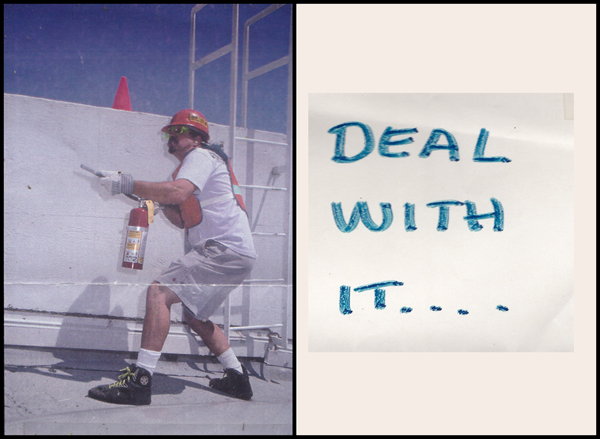

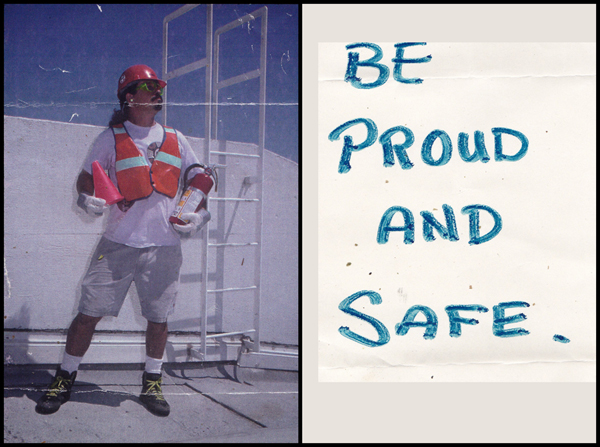

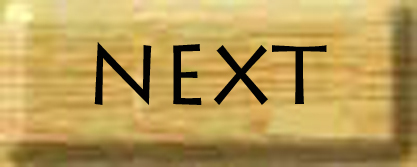

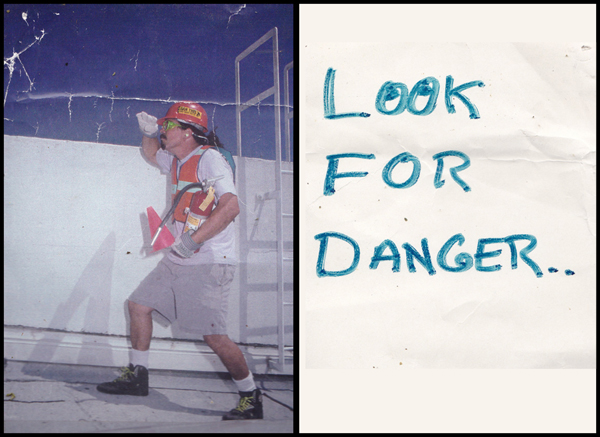

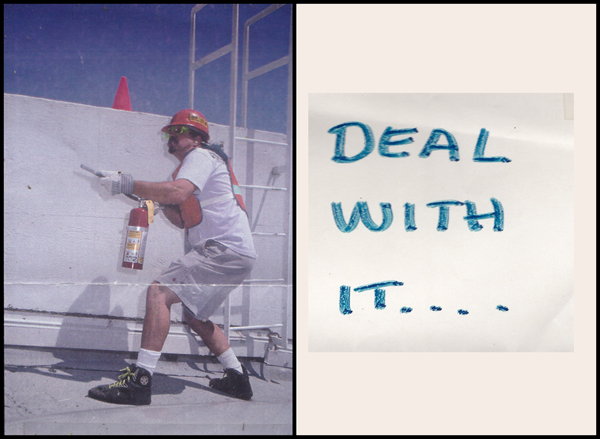

Anyway, Ves had extensive paramedic and fire safety training, and was enthusiastic about helping out with our program. One of the requirements of standard safety compliance is putting up posters around the workplace emphasizing safety awareness in some way. Ves was always looking for ways to make everything more fun and lighten my load, so he created a series of comic safety awareness posters around the plant with himself posing in hardhat, reflective vest and fire extinguisher as "Captain Safety," on the lookout for hazards. The class clown of Facilities.

Probably the most useful part of the safety program was the first aid training. After "shit happens", comes, "What do you do about it?" The American Red Cross provides first aid training as part of their basic mission, and if you gather together enough students and a room to meet, they will set up courses and provide instructors, literature, props and CPR dummies. The training was open to anyone interested, and my goal was to have at least two workers from each department learn the time tested methods of stopping the bleeding, restoring the breathing and dealing with heat stroke, heat exhaustion and shock. Later on, when the SkateZone was up and running, those who had jobs in the park were required to have taken the first aid course, with emphasis on broken bones and concussions. It came in handy.

Now here's the strange thing about skateparks. Take the way it is now. Outdoor concrete skate-at-your-own-risk skateparks are everywhere. The municipality posts some rules about having to wear helmets and pads, and park hours; but pointedly, there is nobody there to enforce them. Unlike a swimming pool, there is no lifeguard; if there were, anytime someone was injured with no pads, the municipality would be liable. Unsupervised, it is the skater's own responsibility to follow the rules...or not.

The SkateZone existed before this enlightened age and to protect the company from liability, the park was not billed as a retail recreational business, but first as a training facility for our professional team and aspiring amateurs. Expanding on that idea, SkateZone became a private club. Membership was organized into a database, and each skater was given a picture ID, like the ones we saw being made at Kevin Harris' Skate Ranches in Vancouver. If skaters were under 18, they had to provide a notarized permission slip and liability waiver from their parents. In their individual files there were the names and numbers of who to call in case of emergency. At the entrance to the park, ID's were checked. In this format, the Company did take responsibility and therefore had to enforce the helmet and pad rules. There were many, many exceptions.

Of course there were injuries, mostly twisted and sprained ankles, and broken bones, but in each case, the staff smoothly did the first aid, made the calls, and transported the skater to the ER at Goleta Valley Hospital.

© 2017, 2022 John Oliver

All Rights Reserved

mail@unclejohnsweb.com

In addition to those corny trade shows, Facilities sometimes made props for the videos. For the 1989 video, "Ban This," our creations took me back to my own homemade skate scooter when I was 10 years old. They were well-made versions of the peach-box-on-a 2" x 4" scooter, except instead of two halves of a clamp-on roller skate from the 1940's, in the late 1980's, we had Independent trucks, Powell-Peralta urethane wheels, Bones Swiss ball bearings: the Mercedes-Benz of the Peach Box Scooters. They weren't gray this time, but olive drab army green, matching the theme of a recent trade show. We called them Armored Personnel Scooters.

As time went on, my duties were expanded into more mundane, less fun factory management tasks, and I had less time to be involved with the SkateZone building. I was put in charge of fire prevention, hazardous materials and a company-wide safety program. That kind of made me the in-house building inspector: the Sheriff of PCHQ. I took to wearing my gold "steal-your-face" skull with lightning bolt Grateful Dead tie tack on my shirt like a badge. When the fire department assigned us our own fire marshal to oversee our compliance factory wide, turned out he was a Deadhead too. We got along famously, but he never cut us any slack, and I never asked him to. He would give me a heads up if I were missing something, like if he spotted a cheaper or easier way of accomplishing a result. We teamed up to make the plant a tight ship.

One of the things I had to do was compile an archive of Material Safety Data Sheets, MSDS. There has to be on file an MSDS for every chemical or material in use in the entire factory, so if someone swallows it, or breathes its fumes, or it catches fire, we can look up what's in it right now. I had to call or write to manufacturers to chase down the required paperwork, and keep it all in a big binder. MSDS was a system that had just come into being in the mid 1980's for manufacturers, and some companies were unaware of the OSHA regulations. At one company, skeptical people I spoke to on the phone kept transferring me up their chain until I reached the CEO in a meeting with some of his managers. They put me on the speakerphone and grilled me about this so-called MSDS thing, and why I needed to know what was in their product. They thought I was a competitor trying to steal their trade secrets.

I took a night course in Hazardous Materials Handling at the nearby UCSB extension, so that I could have full knowledge of our situation and how our company fit into the required regulatory system. Others taking the course were a number of employees of Chevron Oil's local operations. Chevron at the time was running TV ads portraying the company as a protector of the environment. A blue butterfly fluttered over a seaside sand dune. A chain-linked fence had been erected to separate 2 acres of dunes from the 1000-acre El Segundo refinery, site of many, many leaks, spills and explosions, polluting the air and the groundwater since 1911. A voiceover asks, "Do people really go out of their way so a tenth of a gram of beauty can survive?" The fuzzy, warm feel-good voice answers itself, "People do," proclaiming themselves saviors of the endangered "El Segundo Blue."

The Chevron employees were pretty funny whenever the topic under discussion somehow produced a straight line. Sometimes by accident and sometimes on purpose, the instructor would phrase the current topic in a rhetorical question. "Do some toxic waste producers cut corners and cheat on disposal regulations to save money?" The Chevron managers would chant their punch line in unison, "People do," and cackle cynically.

Then there was the mandatory company safety program. Companies with even a few employees are required to have an active program to keep the workplace safe and the workers safety conscious. In the construction world, every small contractor is supposed to gather his crew periodically for a "tailgate meeting" to discuss safety matters, but they often don't bother.

Whenever it turned out that I was asked to conduct a safety meeting, my idea was to bring everybody into the awareness that 'shit happens" by going around the group and telling our goriest construction accident stories. It's amazing how many people get shot with pneumatic nail guns, often in the head. Those things can be set to "bump fire,' so that if you continuously hold the trigger down, it will fire a nail when you bump the tip against the wood and you can go faster. So if you're coming down the ladder with the trigger still pulled after nailing off some framing, your buddy is standing there holding the ladder and you're both looking the other way, BANG! He's got his hard hat nailed to his skull. I have shot one of those framing nails into my finger, cut another fingertip with a Skilsaw, fallen from high places, but I still have all my parts. Some of the craftsmen I admired most had shortened fingers due to a momentary misjudgment in the use of power tools. One moment, ZIP! and your fingertip is gone forever. No putting it back on, it was turned to hamburger. If those kind of stories give you the willies, that's the goal. Once everyone had gotten the willies, the safety meeting had served its purpose. Moving on.

In the PCHQ setting, that kind of safety meeting was appropriate for the production workers in their environment of powered machinery, but the office staff and cubicle workers have different hazards. The most common office accident is the bottom drawer of a filing cabinet is left open. Who knew? The drawer is left open and someone carrying a piece of paper or something doesn't see and trips over it.

We learned a lot about Ves' past when we took that Noodles tour to Nor Cal. After we left Derby Park in Santa Cruz, he guided us up the Loma Prieta Ridge, a small, forested mountain range running up the peninsula toward San Francisco. He had been a firefighter and driver for Cal Fire in this area, and had stories to tell about driving their equipment through impossible terrain. After that he had worked as an ambulance driver until he couldn't take it anymore. Responding to traffic accidents, he said, you get used to the gore, and the physical pain you're witnessing, and even the death; you have your training for that and you do your job. The thing that weighed the heaviest on ambulance drivers is the grief of the survivors. Ordinary people had been driving along on an ordinary day, when, BLAM! Suddenly their companion, or their parent, or child, or spouse, is dead. That's the hardest pain to witness. Or to do anything about.

Anyway, Ves had extensive paramedic and fire safety training, and was enthusiastic about helping out with our program. One of the requirements of standard safety compliance is putting up posters around the workplace emphasizing safety awareness in some way. Ves was always looking for ways to make everything more fun and lighten my load, so he created a series of comic safety awareness posters around the plant with himself posing in hardhat, reflective vest and fire extinguisher as "Captain Safety," on the lookout for hazards. The class clown of Facilities.

All Rights Reserved

mail@unclejohnsweb.com